Our research has discovered much about Sgt. Holland, but not as yet anything of his birth or early life. The fact that he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal was a very great honour and reflects his quality of service to his country in the Regular Army. It is possible that a descendent still lives in the area of Hollocombe, but nothing has been firmly established, and we look forward to the possibility that descendents might make a contact. It appears that neither Sgt. Holland nor any relatives were living in the Winkleigh parish before or at the time of the 1911 census and he himself might already have been serving in the army, so that his association with the village must have begun not too long before September 1914. The first list of Winkleigh men serving was posted on the church notice board in September 1914, and it contains the name of ‘Walter Holland, Devonshire Regiment’, already serving in the regular army. Although a newcomer, the village was proud to ‘claim him as one of our own’ when the Chumleigh Deanery Magazine reported in December 1915 that Winkleigh welcomed home Sergeant W.R. Holland, Devonshire Regiment, who was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for bravery.

‘Winkleigh is proud to claim him as one of her own. The Devonshire Regiment is one of the finest in the British Army, and has a great and well deserved reputation, and we are indeed proud to know that our local men are helping to make that reputation even higher than it was before.’

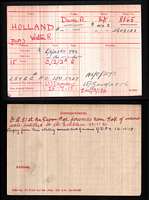

It is very useful that Walter was awarded two medal cards, both attached to this account. The first card, issued as a result of the award of his DCM on 16th November 1915, shows that the medal was given as a result of his bravery at the battle of Loos on 25th September 1915, serving in the 8th Devons, a Kitchener Service Battalion. His other war medals, the Victory, British War medal and 1915 medal are recorded on the second medal card, issued during the war. The low four digit number on the first card recording the award of the DCM is his number on joining the regular army some time before, which he retained on being posted to the newly formed 8th Battalion. This card also gives us the important information that later on (sadly date not recorded) Walter was promoted to the rank of Warrant Officer, and at this point given a new number 5608133.

No records of Walter’s service career have survived the London blitz, but the fact that by 1915 he had already been promoted to Sergeant is an indication that he must have been very highly regarded. The 1911 census has no traceable record of a Walter Holland of the right age or background anywhere in the country, this fact indicates that he was already serving in the army, stationed abroad. It is possible that Arthur had enlisted in the regular army and if he was serving with the 1st Battalion, who at the start of the war were stationed in Jersey, he could have been one of the NCOs posted to the new battalion as part of the very valuable nucleus of NCOs required to begin the training of the new recruits enlisting in ‘Buller’s Battalion’, the newly formed 8th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment that was assembling in Exeter. Kitchener had authorised the formation of the 8th as early as August 7th, and we know from Col. Atkinson’s monumental history of the Devonshire Regiment in the war that the 8th Battalion was originally staffed with Officers and NCOs from the regular 1st Battalion, that was on its way home from Jersey. Walter Holland was there to assist the hundreds of men who were descending on the Exeter barracks, clamouring to be enlisted at once. The announcement on 7th August that the new battalion was to be raised brought a huge rush of men and the resources of the Headquarters were stretched to the utmost, with new recruits, reservists being called up, as well as men clamouring to join the Territorials all arriving at the same time. Senior Officers to command the 8th Battalion were quickly assembled from a variety of resources, Lieut-Colonel Grant from the West African Regiment, and a retired officer of the Devons as second-in command - a man who had refused the command of another battalion in order to return to his old regiment.

Background information on Kitchener’s policy in raising the New Army is attached to this account. The early history of the 8th Devons is typical of the story of the first 80 battalions of the ‘first hundred-thousand’ that were being raised throughout the country, experiencing all the difficulties incumbent on the seemingly impossible task of improvising a New Army without any of the resources to achieve it, driven on by the indomitable will and presence (everywhere seen in the famous poster) of Lord Kitchener, Minister of War. In common with all the New Army battalions, the barracks were overcrowded and uncomfortable, many men their being billeted in the town. Essential equipment, uniforms and rifles were non-existent, and preliminary training was therefore limited, but the novelty of the situation, the enthusiasm, cheerfulness and good-humour of all concerned must have seemed as if ‘the big picnic’ had truly begun. Things became a little bit more organised and serious when in mid-September the Battalion moved to live under canvas at Rushmoor Camp, Aldershot. Young officer material recruits from the gentry and public schools had been sent off hastily to an Officer Training Corps camp at Churn to learn the first basic elements of their work, before attempting to take charge of men, some of whom had served in the army for most of their lives, while the majority were raw recruits.

The History of the Devonshire Regiment (C.T.Atkinson) mentions the origins of these young officers: 6 from Oxford, 3 from Cambridge, 3 from the Artist’s Rifles (virtually an officers training battalion), the rest straight out of the Public Schools, where they had had the experience of their army cadet corps. Their early training over, the senior officers and experienced NCOs continued the work of equipping the battalion with competent subalterns. There were still no uniforms or rifles to be had. Atkinson comments that the men’s ‘appearance on parade, in particular the appearance of their headgear, must have been startling indeed to the professional soldier’s eye.’ Obsolete rifles of the old pattern with short bayonets were the first to arrive for drill purposes, but by mid-October enough Service rifles were issued to equip half the battalion, and those lucky enough to get one were marked off for service if the Germans attempted a landing on the East coast.

By early November, wet, cold and mud were making life at Rushmoor Camp impossible and the 8th moved into Barossa Barracks in Aldershot. Battalion exercises could now complement the endless drill, physical training and route marches. Bits and pieces of uniforms began to arrive and meanwhile the men, totally unaware of what lay ahead were grumbling that they were not already in France! Musketry training could now begin, followed by a move into billets in various villages around Farnham. Again, hopes of moving overseas faded: the 8th Battalion was nominally attached to the 14th (Light) Division, but only as ‘Army Troops’ unattached to a Brigade. However, it was a happy time for the battalion, welcomed and entertained by the local population and with ample training grounds and trench-digging practice provided in the countryside around. A German invasion scare in December was met with huge enthusiasm, and the half-battalion set off in pouring rain to meet the foe, only to be turned back and wet to the skin to return to headquarters to be met with the good-natured jeers of their comrades!

In March 1915 the 8th returned to Aldershot to be now fully equipped with rifles and other necessities, and to conduct Brigade and Divisional exercises (still attached as ‘army troops’) but confident they would not be left behind when the 14th Division embarked for France. The time for the first New Army battalions to be sent was fast approaching. Everyone was aware that after a long winter in waterlogged trenches the 2nd Battalion of the Devons experienced dreadful casualties on 10th- 14th March at the British offensive at Neuve Chapelle: 10 officers and 274 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. The 1st Battalion too, in the south-east of the Ypres sector were to suffer great losses in April defending Hill 60. The Territorials were not available – they had already embarked for India. The 14th Division left for France but the 8th Battalion (and the second Service battalion to be raised, the 9th), remained in England until the end of July. Instead, and transferred to Basingstoke they were tasked with striking canvas and clearing up the mess left by another Division going overseas, but finally and to everyone’s great enthusiasm orders were received on July 17th for embarkation leave and a return to Aldershot. On 25th July the two Battalions entrained for the journey to Southampton for embarkation, the band of the 11th Hussars playing them down to the station. The 8th and 9th Battalions were destined to join the 20th Brigade of the famous 7th Division, and they served together for the next three years taking the place of two Guards’ battalions posted to join the newly formed Guards’ division. To replace two battalions of the Guards in the 20th Brigade, in such an elite Division, was an honour indeed, keenly felt by the Devons. The 7th Division was at that time in the line in the Neuve Chapelle sector, now a quiet area of ‘live and let live’, with the normal trench routines enlivened only by wiring parties and occasional sniping, and with very few casualties.

The battle of Loos lay ahead. The 7th Division moved South In September, the 8th and 9th Battalions taking position on a front due East of Vermelles with its right resting on the Vermelles – Hulluch road and the famous Quarries directly in front. Vast preparations were in progress for the ‘Great Push’, of which the Germans were of course very well aware: at the behest of the French the battle was to take place in an area totally unsuitable for a frontal attack over flat and open ground, with inadequate shelling that could not cut the German wire. In so-called ‘reserve’ just before the battle began on September 25th, the 8th and 9th Devons spent the time digging new forward trenches, saps, communication trenches and just before the battle bringing up into the forward line the heavy gas cylinders that were to be discharged in the hope that the 1st line German trenches would be overrun without great casualties. Unfortunately, when the advance began at 6.30 am, (see attached map) the wind blew the gas not into the Germans, but along the line of our own front incapacitating many whose only protection were the so-called smoke helmets whose talc windows quickly became blurred and useless. In the 8th, by an oversight, ‘A, ‘’D’ and ‘C’ Companies moved forward together, crowding the gaps in the British wire and presenting great targets to the Germans, but their objective, Breslau Trench, was taken 12 minutes into the assault, followed by the Breslau reserve trench. Casualties were horrendous, and by now only three officers remained standing. The Germans were abandoning their positions and both the Cite St. Elie and Hulluch were there for the taking, but no reinforcements arrived and without them the Devons could do no more. The 9th Devons had pushed on towards Gun Trench where on the arrival of the 8th the Devons succeeded in capturing a battery of field-guns, but they too could go no further than the Hulluch crossroads, and later in the day were forced back to the chaos of Gun Trench. A German counter attack on Gun Trench almost succeeded but was repulsed after fierce hand-to-hand fighting, but the 8th Battalion now amounted to little more than remnants, mixed up with the 9th and the remains of a battalion of Scottish troops from a brigade of the Second Division. The position was precarious: at the end of the line the Quarries had been retaken by the Germans. Overnight about 50 men of the 8th took a position on the south side of the Vermelles-Hulluch road where they remained on the 26th, while a similar group were in position north of the road. To their left the line was held by the 9th battalion. In the evening the 9th were withdrawn to their old start line trenches and those that were left, numbering fewer than 150, must have felt all had been in vain. Here they remained in support until 29th, when they moved back to billets in Beuvry.

The Devons had been wiped out. The 8th Devons lost 620 men and 19 officers killed, wounded or missing at the battle of Loos, a tragic end for all those who had so eagerly rushed to join ‘Buller’s Battalion’ in August 1914, and who had so ardently longed to get to France during their months of training. Indeed, the innocence of Kitchener’s New Army had been betrayed at Loos. After the 1915 battles of 2nd Ypres, Neuve Chapelle, Aubers, Festubert and Loos, the old regular army had virtually gone, the Territorials were now fully engaged, and the first battalions of the New Army had been mauled. Conscription and with it the harder and more cynical mood of 1916 were inevitable. The story 8th and 9th Battalions of the Devons are a typical example of the terrible wastage of 1915, ‘the year of hope’.

In the 8th on the 30th September, 6 officers and 263 men answered the roll-call, and we hope that the survivors took some pride in their battalion that had done all that could be asked of it. Very few battalions could boast that they had captured German guns, but the 8th were there with the 9th to secure these trophies. Atkinson quotes the account of one survivor of Loos:

‘The men were simply splendid, as steady as veterans: they neither flinched nor grumbled the whole time, though they were cold, hungry and tired to death, as well as wet to the skin.’

Two of the guns that were taken in Gun Trench were presented to the County of Devon, and on November 12th were formally handed over for safe keeping to the mayor of Exeter, to be displayed at first in the cathedral precinct. At the official parade, 6 officers and 40 men of the two battalions formed a guard of honour, together with a detachment of the 3rd Battalion, the Territorial Provisional Battalion, the Yeomanry and the Territorial battery. A newspaper report of the ceremony is attached to this account.

Among the few surviving NCOs in The Battle of Loos, Walter Holland was awarded the DCM for his bravery. The Citation dated 16th November 1915 tells us exactly what he was doing:

8865 Sgt W.R. Holland 8th Battalion

For conspicuous gallantry on Sept.25th near Hulluch. Although wounded in the thigh in the advance from our front line to the front German trench, Sgt. Holland ran out a telephone wire 500 yards further forward to a position near The Quarries, and kept the front line in communication with the Brigade Headquarters throughout the day. He displayed great coolness and bravery, and his devotion to duty offered a fine example to all ranks. 16.11.15

Battle experience led to orders to ensure that battalions would leave behind a number of men when going into action, to form a nucleus for rebuilding, in the event of heavy casualties being suffered. A total of 108 all ranks, consisting of a mix of instructors, trained signallers and other specialists, were to be left out. The clue to Sgt Holland’s survival in the battle is that of his role. The Citation shows that he was obviously attached to Battalion Headquarters as the signalling Sgt. and thus avoided taking part in the frontal assaults of ‘A’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies or in the later advance by ‘C’ Company that had been in reserve. Battalion HQ included the Regimental Sergeant-Major (RSM, the most senior Non-Commissioned Officer) plus a number of specialist roles filled by Sergeants: Quartermaster, Drummer, Cook, Pioneer, Shoemaker, Transport, Signaller, Armourer (usually attached from the Army Ordnance Corps) and Orderly Room Clerk. With him as Signalling Sergeant, Walter Holland would have had in his section a Corporal and up to 15 Privates. Since the Quarries changed hands several times during the battle, it was vital that Brigade was kept fully informed of the situation via Battalion HQ. The signalling observation post and telephone lines had to be kept functioning throughout the continuous shelling.

Following Loos, the 8th Battalion found itself transferred to the Somme area, early in December, after a period of immediate recuperation around Givinchy. The 20th Brigade was now commanded by a ‘fire-eater’, General Deverell. Fortunately, Givincy was an area of ‘live and let live’ - it had to be because on both sides the trenches were flooded, and many ‘posts’ were merely sodden islands surrounded by water. It was a miserable place, trench foot a constant threat involving daily treatment by rubbing the feet with whale oil to keep out the wet. New drafts arrived - over 400 men in the first fortnight of October, and by the time the battalion reached the Somme it already numbered 25 officers and 695 men. More men arrived in December and January so that by February it was well up to strength. Training of these recruits was constant, the senior NCOs carrying a huge burden in instructing the men both in trench warfare and the specialist roles of machine gunners, signallers, bombers and so on. The 7th Division lines on the Somme ran from Bray-sur-Somme on the left, its centre at Morlancourt and the right at Meaulte. In front of the 20th Brigade lay Mametz on the right, Fricourt on the left, names that will resonate forever in the history of the Battle of the Somme. Behind it rose the higher ground of Delville Wood, Longueval, the Bazentins and High Wood, destined to be the sacred ground of the 7th Division.

Meanwhile the Somme was one of the quietest places of the front: no fighting but a time of incessant hard labour repairing waterlogged trenches and building roads and light railways for the coming offensive. The 8th Battalion trenches were in a deplorable state with insufficient wire, parapets barely bullet-proof, and communication trenches merely shallow waterlogged ditches. Of course as soon as new earthworks were built the Germans attempted to knock them down again, while at the same time ascendency had to be gained over German snipers and the control of no-man’s land. The Germans made full use of their rifle-grenades, which together with Mills bombs had now begun to arrive for the British army, demonstrating the importance of these weapons to take a potential toll of front-line casualties, and of the importance of deep dug-outs and well revetted and sandbagged trenches to avoid them. Luckily from October 1st 1915 to June 30th 1916 the battalion lost only three officers, two killed and one wounded, and no casualties at all of men while in the line.

The Divisional rest from 7th to 25th December included Christmas festivities, with the men eating Christmas dinner at 2.30pm, the WOs Sergeants at 7.00 pm and the Officers later. The Mayor of Exeter visited the battalion on 20th and no doubt welcomed the recent big drafts of recruits and returners who we know were building the battalion for the next slaughter - but all of course who now required intensive training. By 1st January 160 new arrivals had been recorded and they were inspected by the keen eyes of Brigadier Deverell before being complimented by him on their performance on a 15 mile march in full equipment. Further drafts, gas drills, rehearsing the attack and night operations were relieved by cross-country races (the 8th taking 3rd prize and a 50/- reward, no doubt spent on extra beer).

With Sgt. Holland’s war records lost we cannot follow his story further in any detail. The 7th Division was fully involved in the years ahead, the 8th and 9th Devons remaining with the 20th Infantry Brigade, taking their part in the 1916 battles of the Somme, the Arras offensive in 1917 with flanking operations around Bullecourt, and then the whole Passchendaele offensive. At the end of 1917 a major change now occurred with 7th Division being one of five British formations selected to be moved to Italy. This was a strategic and political move agreed by the British Government at the request of the Allied Supreme War Council, as an effort to stiffen Italian resistance to enemy attack after a recent disaster at Caporetto. Many diaries at this time, by men who had witnessed slaughter in the floods of Passchendaele, talk of the move and Italy as being "like another world". Much work was done preparing to move into the mountainous area of the Brenta, but eventually the Division was instead moved to the line along the River Piave, taking up positions in late January 1918. In October 1918 the Division played a central role in crossing the Piave, the Battle of Vittoria Veneto and the eventual defeat of Austria-Hungary.

16 July 2011